An extract

My family moved from Leytonstone in east London to Canvey Island in Essex in 1950, when I was six years old, and my brother a baby. Our father rented a small timber bungalow in Grafton Road, only a few hundred metres from the sea wall, then moved us all to Hadleigh, a small town several miles further along the Thames coast. On Canvey Island I spent a year at Long Road Primary School, a fine red-brick building – still in use – surrounded by dykes originally excavated by Dutch engineers. These were rich with dragonflies and other astonishing insects and small reptiles, in amongst the almost impenetrable bull-rushes and other rampant marshland vegetation. The bungalow which became our home for a year was one of many thousands of ‘jerry-built’ or self-constructed dwellings created in this frontier terrain, a four-square, single storey wooden house with a verandah, erected on brick piers about 15 inches off the ground, high enough for a toddler to crawl under from one side to the other, which of course I did. Every house in our unmade road was different, often eccentrically so. The wider landscape had a uniquely industrial, estuarine character that was thought to be uncultivated, even wild – as were the inhabitants, it was said.

Moving to Hadleigh we found ourselves living next door to a chapel belonging to The Peculiar People, a Christian sect unique to Essex, active for much of the 19th and 20th centuries until it joined with the Union of Independent Evangelical churches in 1956 The people who settled in this part of Essex often embodied a pioneering spirit, and a nonconformist religious and political scepticism, still evident. Nothing, I came to realise, was ever quite as it seemed in this extraordinary county. Years later, after I met my future wife at a folk club in Southend, her own father having moved from London’s Jewish East End in the 1930s, we discovered that, separately and together, over the years, many other people we knew came from similar patterns of migration, from London and beyond. The life of the poet, Denise Levertov, born in Ilford in 1923, acutely registers these migrations and shifting religious and social allegiances. She was the daughter of a Welsh mother and a father who was born a Russian Jew yet became an Anglican priest. Levertov carried her memories of the rivers and gardens of Essex for the rest of her life, despite settling in America where she became one of its most renowned writers, later converting to Catholicism.

The historian Simon Schama, the son of a Jewish family whose father had settled them near Leigh-on-Sea, was deeply influenced by the same early sense of place. His seminal work, Landscape and Memory, opens in epic style with memories of a 1940s childhood dominated by ‘the low, gull-swept estuary, the marriage bed of salt and fresh water, stretching as far as I could see from my northern Essex bank, toward a thin black horizon on the other side.’ Schama’s imaginative construction of the Thames was coloured and peopled by the novels of Dickens and Conrad. The young historian in the making was also roused by accounts of Drake’s triumphant return from his circumnavigation of the world in 1580, and Queen Elizabeth the First’s great peroration rallying the troops against the Spanish Armada at Tilbury in 1588. No river or estuary in the world seemed so steeped in drama and history.

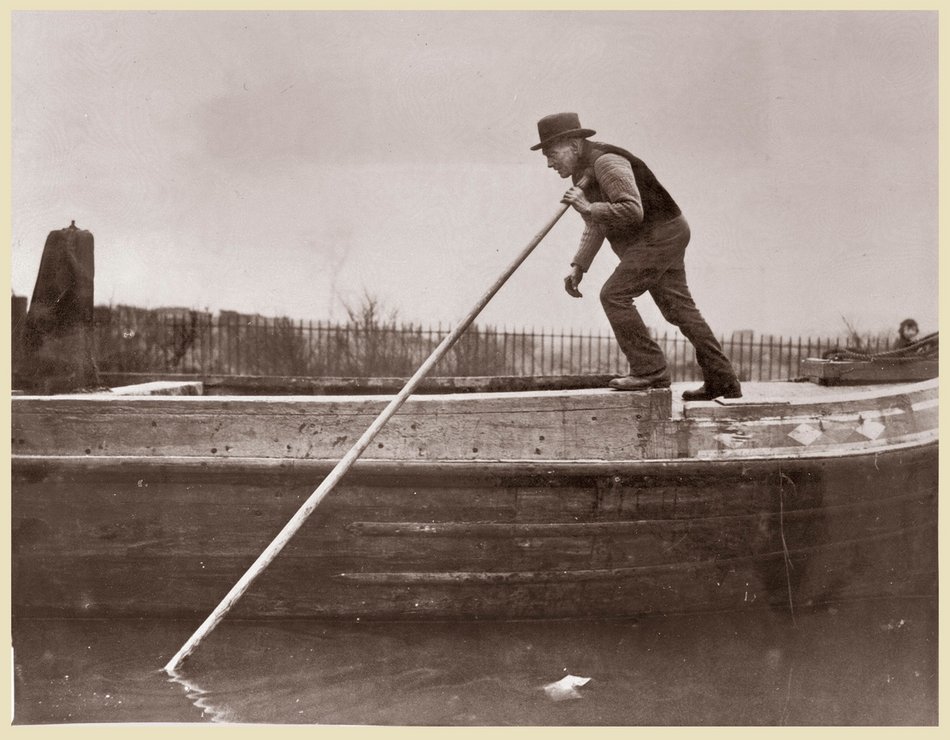

Another writer also haunted by his childhood upbringing on the borders of Leigh-on-Sea and Westcliff-on-Sea was John Fowles. The entry for 2 January 1950, from his subsequently published journals, recalled, ‘A raw, dull day with a wind and all-pervading greyness. The tide full in, and the sea faintly grey-green, ugly. Few people about; at sea the hulls of the small yachts and motorboats wintering at their moorings. No birds but seagulls, resting silently on the sea, or uneasily flying up. The fishing fleet moved out of Leigh into the gloom of the east coast, smacks painted grey and green, with their crews on deck. I envied them for their free life. Old Leigh is a single narrow street, with salty, muddy houses, still retaining snugly the character of fishing and naiveté. The railway line, in this case, preserves the community - its special nature. Past Old Leigh, the cockle-sheds, a dark line of huts. The boat-building shed. The beginnings of the sea wall, the corporation dump, the loneliness. In a sense all nicely divided and gradated. A bleak sort of affection is possible.’

For many the affection is unconditional, becoming a lifelong love. The Essex coastline – more than 350 miles of it – moves from the brutalist to the picturesque, and then, on occasions, to the transcendental. Even those who only know a small part of it (and few can claim to have explored every inch of these shape-shifting, tidal, debatable lands between land and sea), quickly appreciate that it is one of the most complex and historically rich landscapes to be found, particularly so in a county that is bounded on three sides by water, the Thames, the North Sea, and the Stour.

When the 19th century art critic John Ruskin wrote that ‘mountains are the beginning and end of landscape’, he was, on this occasion, wrong. For some of us, it is at the shore’s edge that landscape truly begins and ends, where the land meets and inter-penetrates with the sea and the sky. It is also where many geological eras and human belief systems find their fulfilment or nemesis. In his introduction to S.Baring-Gould’s novel, Mehalah, set on Mersea Island in the second half of the nineteenth-century, Fowles refers to the ‘vast God-denying skies, the endless grey horizon, the icy north-easterlies’ on the Dengie flats in winter.’

For many Victorians the debate about evolution, based as so much of it was on what was being discovered in the fossil record, meant that the sea-shore was a place where revealed religion ended, and self-knowledge began. In the words of the French historian, Alain Corbin, ‘people came to the coasts to browse the archives of the Earth.’ Every beach and smallest of cliff-faces, displayed a geological section or fossil collection that recorded vast eternities of time. This movement from landscape to the interior lives and belief-systems of those affected by it, is a constant theme in the literature and art of the Essex coast and river. The Essex shoreline is a Darwinian test-bed, a place where, if you are looking for something, it will eventually be found, though not necessarily in the shape imagined. These coastal landscapes with their vast skies, uninterrupted horizons at the far edges, glimmering mudflats and estuaries, are distorting mirrors, but mirrors all the same. There are no distractions.

This landscape can be approached in several ways. The visitor can start at the northern limits of the coastline, around Horsey Island in the archipelago of Hamford Water, where Arthur Ransome set one of his most delightful children’s books, Secret Water, then loop round the River Colne, visit Mersea Island, then follow the River Blackwater to Maldon (where the first great epic poem in English, The Battle of Maldon, was written) and out again, past the former Roman fort of Othona, and then on to the remote and eerie Dengie Marshes. Or you might might start at the other end, walking out from London along the shore-paths and factory roads which once ran out to the industrial shoreline of Dagenham, to the oil refineries at Coryton (whose flares and lights at night illuminated the skies of many childhoods), and go on to explore the Victorian Coalhouse Fort at Tilbury, designed to defend London from invasion. After that you will come in time to the ruins of Hadleigh Castle looking out across the downs to the Thames estuary. In either direction, every inch of the way represents territory that has been precariously settled, fought over, and on occasions abandoned, over many thousands of years.

Yet traces always remain. The bones of monkeys, bears, elephants and hippopotamuses have been found in the 300,000 year old river gravels beneath the shingle beaches at Cudmore Grove on Mersea Island. The red earthenware pots which were used by the Romans to evaporate brine to make salt, can still be found in broken piles dotted along the shoreline, particularly along the north shore of the Blackwater. There are Romano-British burial chambers on Mersea Island, the largest of which, Mersea Mount, was 100 feet in diameter and 22 feet high. The remains of Charles Darwin’s famous expeditionary ship, HMS Beagle have been found, it is claimed only recently, in a quiet creek off the Crouch Estuary.

History lies embedded along the coastline in many forms and guises. Much of it is still evident in the names, most obviously with the number of ‘nesses’, and ‘nazes’ as elements of place-names, echoing the Danish word for nose or promontory. The dense white mist along the Essex coast is still called De Ag by some inhabitants, another Danish borrowing. The isolation of parts of the coastline, along with the preservative qualities of mud and salt, give archaeological relics a long afterlife. The Essex littoral, with its profusion of beautiful but strategically vulnerable rivers and estuaries – especially the Stour, the Colne, the Blackwater, the Crouch and the Thames – has provided a bulwark of English coastal defences, the foundations or ruins of many still visible. Facing out to the North Sea (in Victorian times often called The German Sea), the eastern reaches have provided the first line of defence against invasion.

This coastline embodies a melange of the maritime and the industrial, the defensive and the arcadian, much of it now redundant, and gaining a disputed etymology of its own: slack nature, post-industrial wilderness, unofficial countryside, working wild, drosscape, edge condition, terrain vague. It is this potent mixture of economy and geography that confounds and dismays contemporary landscape aesthetics.

Debates about landscape aesthetics are now gaining urgency, even if the UK’s endorsement of the European Landscape Convention (Florence 2000) in 2006 caused scarcely a ripple in the political press. Article 5 states that, ‘Each party undertakes to recognise landscapes in law as an essential component of people’s surroundings, an expression of the diversity of their shared cultural and natural heritage, and a foundation of their identity.’ This growing appreciation of the importance of place now goes to the heart of politics and to issues of popular aesthetics and cultural identity. Yet consensus is hard to find on what is valued and what remains unloved. A survey of the landscape qualities of the English counties which the magazine Country Life published in 2004, awarded Essex no marks at all for landscape quality, a judgement unsurprisingly resisted by those who live there.

Furthermore, because so much of East Anglia is marshland and estuary, sky and water, the chromatic range on the east coast is quite different to that found elsewhere in Britain. Edward Bawden, who along with Eric Ravilious adopted Essex and made an art out of its ramshackle farm outhouses, small-holdings, and bleak winter fields, said that the approach of Spring filled him with horror, knowing that everything would turn green. Both preferred the browns, russets, mauves, greens and muted colours of the furrowed fields, decoy ponds and fens of East Anglia in winter. In doing so they created a sensibility – part aesthetic, part bloody-minded – that contributed an enduring element to the muscular style of 20th century English art.

Ken Worpole

Reproduced by kind permission of the author. Extracted from 350 Miles: An Essex Journey, a collaboration with photographer Jason Orton (2005), and ‘East of Eden’ in Towards Re-Enchantment, edited by Gareth Evans & Di Robson (2010).